![[The Nicks Fix]](nxfxsmal.gif)

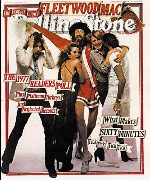

Rolling Stone

January 12, 1978

Issue 256

by Dave Marsh

There is nothing mysterious about Fleetwood Mac sweeping Rolling Stone's 1977 Readers' Poll. Rumours,

the album that topped the charts for six months, has sold almost 8 million copies and still sells over 200,000 copies weekly. Released in February, Rumours sold enough copies at its peak to go gold twice a month, platinum every thirty days. (They've also got a platinum eight-track and gold cassette). Four of the album's eleven songs have become hit singles: "Go Your Own Way," "Dreams," "Don't Stop" and most recently, "You Make Loving Fun." Over in Burbank, the biggest problem the band has created for its record company, Warner Bros., is deciding whether to release a fifth single. Should it be "The Chain" or "Second Hand News," or should they forget about it altogether to avoid saturating the market?

There is nothing mysterious about Fleetwood Mac sweeping Rolling Stone's 1977 Readers' Poll. Rumours,

the album that topped the charts for six months, has sold almost 8 million copies and still sells over 200,000 copies weekly. Released in February, Rumours sold enough copies at its peak to go gold twice a month, platinum every thirty days. (They've also got a platinum eight-track and gold cassette). Four of the album's eleven songs have become hit singles: "Go Your Own Way," "Dreams," "Don't Stop" and most recently, "You Make Loving Fun." Over in Burbank, the biggest problem the band has created for its record company, Warner Bros., is deciding whether to release a fifth single. Should it be "The Chain" or "Second Hand News," or should they forget about it altogether to avoid saturating the market?

Multimillion monsters have become commonplace in the record business. Consider the history of the gold and platinum awards the industry (through the Recording Industry Association of America) makes for LPs that move heavy tonnage. Prior to 1969, only gold records (for $1 million in sales, about 450,000 copies) were awarded. That year, Atlantic gave Cream's "Wheels of Fire" the first unofficial platinum record (for sales of one million units or more). Unsanctioned platinum awards appeared sporadically for the next several years despite RIAA protests. But in 1975 the RIAA raised the gold standard to 500,000 units to compensate for increases in wholesale record prices, and because of the increasingly large market was forced to officially sanction platinum. Platinum has replaced gold as confirmation of star status, and record companies advertise LPs as double, triple and soon (who knows?) octuple platinum.

In 1976 the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, Boston, Peter Frampton, Boz Scaggs and Stevie Wonder each released records that sold more than 3 million units. Fleetwood Mac, the album that preceded Rumours, sold well over 3 million units, but finished in the middle of the pack, despite being the largest-selling record in the history of Warner Bros., a company that hasn't exactly slumped for the past decade.

What no one has been able to determine is what separates Fleetwood Mac from the rest of the pack. However, certain things are obvious. In the first place, they are the most spectacular illustration of the theory that every admirable but unsuccessful artist in Sixties rock is succeeding in the late Seventies: Boz Scaggs and Bob Seger are other prominent examples. In addition, Fleetwood Mac has become America's most successful band without creating any perceptible rancor. Always critics' pets, they continue to receive excellent reviews. None of the cheap shots that were taken at Peter Frampton have been aimed at Fleetwood Mac. This has something to do with their attitude. David Young, a youthful Warner Bros. LP promotion man, remembers driving away from the 1976 Kirshner Rock Awards where Fleetwood Mac had been acclaimed, though hardly so heavily as this year. "Christine McVie got in the car with us," Young recalls, "and sort of looked around. Then she said: 'Are we stars?' "

Mick Fleetwood puts it another way. "You won't catch us selling Fleetwood Mac medallions on our next album sleeve," a thinly veiled jibe at Frampton's "I'm in You" LP, which was as choked with merchandising offers as a late-night TV show. Fleetwood speaks of maintaining taste and integrity with a passion that seems fresh because everyone else seems to have left theirs in the Sixties.

This quality of humble amazement and the group's determination to remain that way combines quite nicely with Fleetwood Mac's stature as the only self-managed rock giant. The Eagles are Svengali'd by the redoubtable Irving Azoff; Linda Ronstadt has Peter Asher; Boston is guided by a consortium of music-business experts; Peter Frampton has the advantage of Dee Anthony's twenty-five years in show business manager, and Stevie Wonder has the Motown organization behind him.

Fleetwood Mac is managed by its drummer.

Mick Fleetwood sits in his wheelchair quite naturally, considering that he must double up his six-and-a-half-foot body to get into it. But his arms jut out at awkward angles while he spins around a cavernous sound stage in the Hollywood Studio Instrument Rental complex.

Fleetwood has no need of his wheelchair, though it would be difficult to know it's only a prop unless you'd seen him walk over and unfold it. He's clearly enjoying this toy -- a natural reaction of the transplanted Californian to anything vehicular (perhaps it is true that, in Wilfred Sheed's phrase, "Englishmen who go to California never recover"), or maybe he enjoys posing as an invalid at a moment when things have never been better and are becoming more so every day.

It's a far cry from the turmoil Fleetwood Mac knew only a year ago. For now, the rumors of disintegration have virtually disappeared. John McVie is at his home in Hawaii. Christine McVie and Stevie Nicks are off somewhere, presumably packing for the group's tour of the Orient and South Pacific, but definitely incommunicado. Lindsey Buckingham is rushing to finish the production of Walter Egan's second album. (Buckingham and Nicks helped co-produce Egan's first.) And Mick Fleetwood, the band's cofounder, drummer and manager, is sitting in a wheelchair, auditioning keyboard players for a group led by Bob Welch, the guitarist who left Fleetwood Mac more than three years ago, creating an opening for Buckingham and Nicks, the very situation that made Fleetwood Mac millionaires.

Perhaps a quick update of Fleetwood's faintly Byzantine history is in order. Formed in 1967 by three former members of John Mayall's Bluesbreakers (drummer Mick Fleetwood, bassist John McVie, guitarist Peter Green), the band's original intent was to play blues more purely than Mayall would allow. Initially, they were joined by two other artists, Jeremy Spencer, a rowdy somewhat in the Keith Moon tradition, and Danny Kirwan, a more pop-oriented young Englishman.

Green left the band in mid-1970 to join a Christian fundamentalist sect, but not before contributing the group's first European hit, "Albatross." (It never dented the American Hot One Hundred.) That summer McVie's wife, Christine, joined as keyboardist and occasional songwriter. Spencer left to join a similar Christian group in late '71, and was replaced by another mainstream musician, Californian Bob Welch.

Each change pushed the group closer to mainstream rock. When Kirwan left in '72 and Welch exited in '74, what was left was an R&B rhythm section (Fleetwood/J. McVie) and a singer/songwriter in the Carole King mold (Christine). As if to complete the transition, replacements were found in Lindsey Buckingham, a guitarist who wrote, and Stevie Nicks, a writer who sang, refugees from upperclass San Francisco suburbs.

Other crises were intermingled with the personnel changes, of course. The worst was the time in 1973 when Clifford Davis, the group's first manager, fell out with them and put an ersatz group on tour under the Fleetwood Mac name, causing both confusion and litigation. The real group won its suit and continued, with Welch, Fleetwood and John McVie sharing the managerial reins. After Welch left and McVie withdrew, Fleetwood continued with the job. "I just sort of took to it, liked doing it."

Fleetwood says making decisions for five people is fairly easy, mostly because the group shares essentially the same instincts. This struck me as another relic of the Sixties, but it clearly works. During the recording of Rumours the stories of strife between Buckingham and Nicks and John and Christine McVie led to a great deal of speculation about how long the band would stay together. But the dissension had nothing to do with business, however much it may have gotten in the way. As Warner Bros. Creative Services Director Derek Taylor puts it, "They DID continue to sing on one another's songs."

"We're much less insulated," Fleetwood explains, "because I make sure everyone knows what's going on. An outside manager has a tendency to try to make it look as though everything is going smoothly even when it's not.

"I'm not recommending it; I think it's a slightly unusual situation. You can imagine, when the band started to do noticeably well, I can't name how many people, including what were probably some very talented managers, approached us. We just chose not to have anyone poking their nose in; we felt we could do it on our own.

"Apart from that, I think we've got complete peace of mind. I think, for instance, that if someone from outside had been handling the band, we probably would have broken up when there were problems. This band is like a highly tuned operation and wouldn't respond to some blunt instrument coming in. There's a trust between all of us that would make that a problem."

One of the places where self-control was most telling was in the making of Rumours itself. The album took eleven months to finish, which would have panicked Warner's had Fleetwood Mac not continued to sell so strongly. But according to Fleetwood, the sessions took so long not because of personal strife, but precisely because everyone sensed they were poised for a breakthrough.

"We felt once we'd done the tracks that all the material, the way WE looked at it, was very strong. For us -- which is the bottom line," says Mick. "From that point, if it had been a little shaky, we might not have spent a lot of money recording it. But we felt it was warranted because we were working on making what was good better and better and better and better. And the record company was really very good. They called a couple of times about hearing things and I said, you're not hearing ANYTHING till we've finished. They said, 'You realize how much money you're spending?' We did, we were very aware of the money.

"Had there been an outside manager, I would say we would have been hustled more. He would be finding out about how much money we were spending, and tend to feel a little intimidated about the money. Again, as musicians and players, that's what we wanted to do. We were gonna get this thing pretty much how we wanted it -- as near as you can ever get. And we did."

Mick seems proud of the band's surprising lack of arrogance, a common reaction to new success among rock groups that is often abetted by management, which likes to make it clear, not just to the public but also the group, how big time the operation has become.

To the degree that Fleetwood Mac is surrounded by conventional star-making machinery, it does tend to become insulated. Seeking to speak with the group, I was told that everyone was unavoidably tied up, making hasty preparations for their Pacific tour. PERHAPS, however, if I were willing to take a chance at sitting around, for a few hours, or more probably a couple of days, I MIGHT be able to have a BRIEF word with Mick Fleetwood. Of course, no PROMISES were made. In the end, Fleetwood was far too courteous to keep me waiting.

None of this adequately explains the difference between selling 8 million records and, say, 3 million. But nearly everyone I spoke to at Warner Bros. denied anything special had been done to sell Rumours. Mostly, everyone agreed with Derek Taylor's summation: "Stay in stock, stay on top of ads, spend the TV money at the right time, keep the singles coming." Sales and promotion chief Ed Rosenblatt added that part of the reason for the big LP boom was an increase in retail outlets: there are simply more places that sell records than three or four years ago, when the economy was lagging.

But that's too cold-blooded -- if more stores are the answer, why not platinum Ry Cooder? As Rosenblatt put it, "It's crazy, it's NUTS."

Except maybe it isn't. Derek Taylor has been making up theories about pop music since a new Liverpool group called the Beatles was playing English movie theaters and he has a few about Fleetwood Mac. (Taylor went on to become publicist for the Byrds and, later, press director for the Beatles' Apple Corps). One is that it is greatly to the group's advantage that it has three singer/songwriters; changing lead vocalists helps keep the public from getting oversaturated. This is still a bit too hard-nosed for my taste, but it's getting there.

Taylor's major theory seems almost too pat: "You know, there's no relationship between two nations quite like that between Britain and America," Taylor says in his customarily sedate but slightly crazed fashion. "Look at it: Churchill's parents, Alistair Cooke -- pure British-American, Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy. . . ."

"Jimi Hendrix," I suggest.

"Crosby, Stills and Nash," Taylor counters. And he goes on to explain the individual members of the group as national archetypes. What he calls "the incredible British intelligence of Mick Fleetwood -- he was educated at the Rudolf Steiner School, you know. And McVie is the perfect foil -- he's greatly amused by Hitler, that sort of black humor. Christine is just the essence of a certain type of North to Midlands British. And then we have the flower children [Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham] -- very practical, but also aware that they're sex symbols. It's the best of both countries, really."

This is as thoroughly unsatisfying as all the other theories, and Taylor and I eventually conclude that Rumours is simply a "very, very good two-sided pop record." But clearly, Rumours and this latest incarnation of Fleetwood Mac have some meaning beyond sheer tonnage, and longevity. Even Stevie Nicks' attempt to define it is barely sufficient: "I think it has more to it than just a rock & roll band," she says. "For example, everybody's real interested in the fact that when we walk on-stage, Christine is dressed in her trip, and John is wearing cutoffs and a penguin T-shirt with knickers and vest, looking like Ichabod Crane, and Lindsey's in a suit, and I'm dripping in chiffon. It's weird. All these people look like they're going to a different place.

"There's no continuity in the five people whatsoever, except the spirit."

That's a fine and glamorous answer to what all those Rumours signify. But it is finally as inadequate as saying that Fleetwood Mac succeeded simply by continuing to make records for more than a decade. And anyway, there is continuity here, if not with the band, then outside it. Connections with rock & roll history abound, most notably and disconcertingly, parallels with the Beatles.

Like the Beatles, Fleetwood Mac assembles its songs piecemeal -- a hot guitar here, harmonies there -- and builds them on a firm and powerful blues-based rhythm section. But the excellence of musicianship isn't all there is to it; too many others have that. Fleetwood Mac also writes songs and lyrics that are squarely within the Beatles' romantic tradition -- "You Make Loving Fun" is not so far from the best Beatles ballads.

For this time and place, it is equally important that Fleetwood Mac is the first successful white group since the Mamas and Papas to fully integrate women into its creative framework. It has not been an untroubled process; that's what the rumors were about, in a way. But because Fleetwood Mac made the attempt, its album may speak more clearly than anything else to an audience that's been through similar problems. And that is what finally brought Rumours home in such a massive way. Its songs were made by people not unlike the best parts of you and me: relatively affluent, reasonably honest young adults (or postadolescents, depending). And God knows, there are plenty more than 8 million of those in America. For me, that's admirable enough. Which brings us to the final question, which concerns not what has happened, but what will. All the odds said that Fleetwood Mac should have gone the way of all good British blues bands: broken up after its third album, or struggled on, repeating "Albatross" in gin joints around the world.

Because he is the most objective of the group, it remained for John McVie to sum up the down side of the future. "You always hope it will last indefinitely," he told Record World. "But right at the back of your mind you know that somewhere along the line someone's gonna go, 'Listen, I've got to do something different.' But you always try not to think about that.

"The band would still go on, until it comes to the point where Mick or myself just don't want to do it -- which unfortunately will happen sometime in the far distant future."

Mick Fleetwood seems determined to delay that inevitable moment for as long as possible. He is a businessman by avocation; between management and music, there is no choice. "I'm a musician," he insists.

But ask him what's next for Fleetwood Mac, and he lays out a program. Some people at Warner's suggested that the next project might be a live album -- the group has never done one -- but Fleetwood has a bigger scheme in mind.

"We'll start recording when we finish this tour," he told me, "probably about March. Everybody's already got quite a lot of material loosely together. Stevie's always got tons and tons of stuff -- she writes songs all the time. So basically, we're gonna get down and do some very extensive rehearsals before we go into the studio this time and pick material that we feel is strong. You can never tell -- sometimes things that you think are gonna turn out great in the studio, don't.

"And on a very loose level, we're thinking about doing a double studio LP. We feel that we've got enough material. If there's any filler, then we wouldn't dream of doing it. But that's an exciting thing to at least attempt. It stimulates everyone and it's a challenge. You don't just knock out another album. It's like a real commitment."

Oh, I know, it sounds like a pipe dream. But I also know what Mick Fleetwood predicted for Rumours last summer, when the album had sold only 4 million: "I remember while playing the rough cassette mixes in Sausalito, I said it's going to be much bigger than the last one. I thought it would do like 8 or 9 million." What's weirdest is that it may have been a conservative guess -- which is a nice job of work for people not that much different than us.

| The Nicks Fix main page |