![[The Nicks Fix]](nxfxsmal.gif)

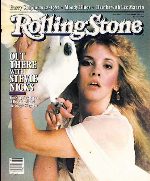

Rolling Stone

September 3, 1981

Issue 351

by Timothy White

Good Fairy Tries to Balance Two Careers -

and Two Personalities

She would rock on the open porches and look at the sea, marveling over its changefulness. There were sunsets when the water resembled hammered gold under the golden light, or it would be running brass or whitely flowering beneath a white sky. Even the storms entranced her. She wanted to cry in ecstasy. She would sing and her marvelous voice would echo in the wild and tranquil evening silence. Dear God -if there is a God in the world- don't Let her know. Never let her know what the world really is.

She would rock on the open porches and look at the sea, marveling over its changefulness. There were sunsets when the water resembled hammered gold under the golden light, or it would be running brass or whitely flowering beneath a white sky. Even the storms entranced her. She wanted to cry in ecstasy. She would sing and her marvelous voice would echo in the wild and tranquil evening silence. Dear God -if there is a God in the world- don't Let her know. Never let her know what the world really is.

- TAYLOR CALDWELL,

Ceremony of the Innocent,

Stevie's Favorite Novel

It is said that the door to the other side of this existence, to the Spirit Corridor and the Plain of Souls, has no knob on it and can only be opened from the outside. You, on this side of the door, must answer the spectral knock with a beckoning, for the Darkness cannot cross your threshold unless it is invited in. And so, on a cool night not long ago in an ancient chateau outside of Paris, there was no rest for a believer.

Fresh from finishing Bella Donna, her first solo album, Stevie Nicks had met up with Fleetwood Mac at Le Chateau, the legendary studio-retreat where Elton John recorded Honky Château and where the Mac were laying down tracks for their next LP. Retiring for the night, Stevie turned off the light in her huge shadowy bedroom. Suddenly, she was startled by the sound of rapidly flapping wings in the blackness. The noise abruptly ceased. Then came a queer whir, and something brushed against her cheek. She froze. The light she had just extinguished sprang on and she was so petrified she could not scream, could not even speak. Ten minutes passed as she cowered in mute terror; then she stumbled down the damp hallway to the room of her secretary, Debbie Alsbury, who calmed and reassured her. She eventually made her way back to her bed and fell into a troubled sleep.

The morning found her still frightened, and as she tried to orient herself, the arched French doors across from her bed swung wide with such force that they toppled the desk standing in front of them, sending Stevie's typewriter, a pair of pink vases and a delicate statuettelike candle sailing through the air.

"I just sat there and watched as these paned doors, two stories high, flew open" Nicks recalls, breathless. "My glass doors opened on a wrought-iron balcony overlooking a wishing well. It was quite dramatic, and the desk went over like whamp! I went into the kitchen, and the people who worked there said it was the ghost of the chateau. 'He is a good ghost, he will not hurt you, he just wants to make himself known,' they said. 'Nothing was broken, was it?'" It was then that Nicks realized nothing had been damaged, not even her slender jade-colored candle, which would have snapped if it had been dropped even at arm's length.

"The place is very old," says Nicks. "You get the sense of what it must have been like to live there hundreds of years ago. It hasn't changed much, and it feels as if it's full of ghosts." She pauses. "If the ghosts are friendly and willing to talk, I am ready to sit down at any time. I would love to."

She folds her arms and is gazing confidently at me from the long couch in the grand fiftieth-floor suite of the spooky Helmsley Palace hotel in Manhattan when something makes her jump. Jimmy Iovine, Bella Donna's producer, has just bumped into a table in the vestibule, causing a shaded candelabra to shake eerily.

"Sorry about that," he says, walking into view. "Oh, God," says Stevie, "that looked like a host." lovine answers with a bemused "Huh?" Her face grows crimson.

"Oh, never mind!" she barks.

She loves fairy tales and believes in spirits and will-&-the-wisps and things that go bump in the daytime and the night. She would like to build her own pyramid and live in a little "witch house" on a cliff overlooking a turbulent sea. Halloween is her favorite night of the year, and although she can't explain the coincidences, certain symbols and words constantly crop up in her life. One of those words is Maya, also known as the Shakti goddess Devi, who represents in Hindu the illusory world of the senses. It's the name of her clothes designer's studios and of the cobbler's shop where she has her outmoded platform boots made. The symbols even invade her sleep.

In fact, the cover of Bella Donna was the result of one of her somnolent brain storms. It looks like a greeting card from the Good Witch of the North: an ethereal assemblage of crystal ball blue mists, silver tambourines and mystic trinities of white roses, with Stevie and a white bird in the center.

"I dreamed that I saw, against a background of blue, a white vertical line, which was me holding a bird," Stevie explains. "At five in the morning I called up Paul Fishkin [her former boyfriend, and founder with Danny Goldberg of her label, Modern Records]. I described to him the image, which became the front cover, and then the one on the back where I've picked up the tambourine and the roses, and I'm looking through the crystal tambourine, which symbolizes a porthole, to see the sorrows of the world. I love the symbolism of the three roses, which is very pyramid, very Maya. The white outfit I'm wearing is the exact opposite of my black outfit on Rumours. Over that it says, Come in from the darkness...The darkness?

"The dark side of anyone, the side that isn't optimistic, that isn't strong. I've got to become stronger because I am very sensitive, and everything really touches me. I love the mysterious, the fantastic. I like to look at things otherworldly and say, 'I wonder what goes on in there?' I think I was a monk in another life. I really do.

"'Bella Donna' is a term of endearment I use," she continues, "and the tide is about making a lot of decisions in my life, making a change based on the turmoil in my soul. You get to a certain age where you want to slow down, be quieter. The tide song was basically a warning to myself and a question to others. I'm thirty-three years old, and my life has been very up and down in the last six years."

To understand Stevie Nicks, it's important to be aware of the yin and yang of her muse. For instance, the original cover for Bella Donna was not quite so ... visionary. Her more grounded nature was in command when she and photographer Herbert Worthington conceived a double-exposure portrait of the two sides of her personality. The photo depicted Stevie's threatening, take-charge yin fiercely scolding the idle, preoccupied yang. Nicks confides that "these two personalities are constantly fighting each other," and adds that she was prejudiced against the first cover because it looked "too heavy, too real." Most of us would like a temporary respite from life's serrated edges, and a few of us have secret gardens of imagination into which we occasionally steal. The difference between Stevie Nicks and the rest of the world is that, given a choice, she usually opts for the never-never land, and she brings along a lunch pail and a pup tent. Stevie says that her favorite fairy tale is Beauty and the Beast. She loved the fable as a child, but when she saw the Jean Cocteau film rendition in later years, her fascination was cemented. She'll recount her version of the yarn at the drop of a hat, claiming that, at the end of the fable, "Beauty became the Beast, and he became the beautiful one."

The story line, as Stevie tells it, concerns the plight of a sweet-natured woman named Beauty, the youngest of three otherwise repellent sisters, who volunteers to become a captive angel in the Beast's castle after her father incurs his wrath by plucking one of his prized roses. Beauty rides to her palatial prison on a magic white horse sent by the Beast and settles into a grotesque lifestyle wherein she spurns the affections of her gentlemanly captor, breaking his heart a little more each day with her increasingly cruel taunts in the face of his love.

When Beauty learns her father is dying, the Beast allows her to go to him, but warns that if she does not return by the seventh day, he will expire from despair. On the eighth day, she leaves her dead father and venal sisters and rushes back to the castle to find that the Beast is done for. In his last breath, he says that all a beast who loves her can do is die for her.

A rather Gothic variation on the Cinderella myth, Beauty and the Beast seems to transcend mere allegory in Stevie's mind. Bewildered by the infinite number of possibilities in life, part of Nicks lets such fairy tales overtake her. (The trappings of this fable entranced Stevie to the extent that while she was at Le Chateau, she rode a borrowed white steed around the phantasmal grounds, her black cape flowing behind her, and almost fell off as the runaway horse threatened to tumble headlong into the crowded parking lot.)

Professionally, Nicks now possesses the means to do pretty much as she pleases. Her solo album and the duet single with Tom Petty, "Stop Draggin' My Heart Around," are selling well, and a tour with a not-yet-determined band is planned, probably ending just in time for her to promote the latest LP by Fleetwood Mac. On a personal level, though, she is beginning to realize that the enemy is within, and she is learning from experience that when fantasy doesn’t fit or suddenly falls away to reveal stark truths, the impact on the dreamer can be acute. "I was most frightened when we finished this last one-year Fleetwood Mac world tour," Stevie says, "because when I decided I had to stop living in the world of rock & roll. That had nothing to do with drugs or anything like that; it had to do with the fact that my life was completely and undeniably wrapped up in Fleetwood Mac. You can call in sick to a job, a boyfriend, even a husband, but you cannot call in sick to Fleetwood Mac--ever. If you have that kind of commitment, you can never really have any other plans for your fife. I've had many relationships in the last six, seven years, starting with Lindsey [Buckingham; her latest is with Jimmy Iovine.] A year in Fleetwood Mac can put a knife in the heart of any relationship because there are a lot of egos. And in relationships, I tend to cop out and say, 'I don't have the time! I’m too nervous! I have to get ready for a show!' Men who would like to take me out, I see it in their faces: 'Boy, is this a job!'"

Nicks' ascent to stardom was sudden. She was working as a waitress in a Beverly Hills restaurant when Mick Fleetwood and John and Christine McVie invited her and boyfriend Buckingham to join Fleetwood Mac. Among Nicks’ personal contributions to the remarkably successful Fleetwood Mac LP that ensued was "Rhiannon," a surging, mesmerizing rocker about a Welsh witch, which, sparked by Stevie's reedy incantations, became a huge hit single. And Stevie herself quickly evolved into a concert cynosure, drifting spacily across stages in gossamer black chiffon, midnight suede riser boots and top hat.

"The princess on-stage is my combination of Natalia Makarova and Greta Garbo and the elegant rock & roll that I love," she says. "It's hard to be a fairy princess fifty percent of the time and just be a nice lady the other half. But I like my real self better. I don't walk around the house in dripping chiffon." (Though throughout out our meetings, she wore chiffon dresses.)

Despite Stevie's vow to slow down, the time intended solely for her "real self" is rapidly being consumed by the effort she's putting into a second musical career. There’s a mighty tug of war being waged inside her, but then burning ambition and the pitfalls that accompany it are a family tradition.

"Dad was real ambitious," says Christopher Nicks, Stevie’s twenty-seven-year old brother, referring to Jess Seth Nicks, who in his fifty-odd years has been president of General Brewing, executive vice-president of Greyhound and president of Armour Foods. He slowed down for a time in 1975 after undergoing open heart surgery, but he now does concert promotion and is building an addition to his own arena in a large amusement park in Phoenix.

"Our father would always be getting promoted and transferred, so we never grew up in any one place," adds Christopher. "We moved from Phoenix to New Mexico to Texas to Utah to Los Angeles to San Francisco. You name it. Just as we were making friends, Dad would come home and say, 'I got promoted!' Stevie had it pretty bum with all the relocation. The move from LA to San Francisco came between her sophomore and junior years. In LA she had just started with her little bands, the first being Changing Times, a four-piece Mamas and Papas thing. They meant a lot to her."

While growing up in the Bay Area, Stevie blossomed as a beauty and came out from behind her granny glasses long enough to become first runner-up as homecoming queen in her junior year at Menlo-Atherton, High School. When the family headed for Chicago in 1968, she stayed back to play with Buckingham in a band called Fritz working (for one day) as a dental assistant and then as a hostess in a Bob’s Big Boy.

"We learned a lot from our father about being strong and not doing anything half-assed," says Christopher, now the promotion coordinator for Modern Records. "But Stevie isn't hardened, and it hurts her sometimes. Although her intelligence saves her, people still take advantage of her. "But," he cautions, "she’ll never lose herself. And we live by the fact that when all else fails, we have our family." And yet time has begun to erode that fortress. Stevie credits her late grandfather Aaron Jess Nicks with her will to sing. An ardent but failed country crooner, he taught Stevie to sing the female parts of call-and-response country songs like Goldie Hill and Red Sovine's "Are You Mine!" while she was still a toddler. Living out of two trailers in the Arizona mountains, AJ, as he was called, was a bona fide eccentric but also a talented guitarist, fiddler and harmonica player. He took Stevie along with him to gin mills to sing and dance as he played. She was about five when AJ had an argument with her parents, who forbade him from taking their daughter on the road for a small tour, and he stormed out of the house.

"He went away for two years and we never saw or heard from him," says Stevie. "I was very upset. I still have a cassette of him and me singing 'Are You Mine'." About a year before he died, in 1973, she wrote a song for him called "The Grandfather Song":

My grandfather taught me to sing at four

Took me everywhere, had me dancing on bars

Paid me fifty cents a week to practice my guitar

Told my mother and father I'd be a country star

Sing like you mean it

Grandfather, put your heart into it

Grandfather, always knew you would do it

Singing timeless country music.

I knew he was going to die," says Stevie, "and I didn't ever play it for him, because there was a line in it that said, 'I can still hear him playing though he'll soon be gone.' I couldn't change that line and I couldn't sing it to him. That was when I decided I would never write another song that I could not play or show to somebody, cause he should have heard that song." (Bella Donna is dedicated to Grandfather Nicks.)

But sometimes loved ones do not live long enough to receive the gifts intended for them. Stevie's beloved Uncle Jonathan was dying of cancer of the colon the week she began working on a composition for him. The night she completed it, John Lennon died. The song was called "For John."

"It was written," she supposes, "in a premonitory sort of way."

Shortly afterward, she began work on "Edge of Seventeen" (title courtesy of Tom Petty's wife, Jane), a song about her feelings toward these tragic deaths.

"The line 'And the days go by like a strand in the wind' that's how fast those days were going by during my uncle's illness, and it was so upsetting to me. The part that says 'I went today... maybe I will go again... tomorrow' refers to seeing him the day before he died. He was home and my aunt had some music softly playing, and it was a perfect place for the spirit to go away. The white-winged dove in the song is a spirit that is leaving a body, and I felt a great loss at how both Johns were taken. 'I hear the call of the nightbird singing..... come away ... come away....'

"I can't believe that the next life couldn't be better than this. If it isn't, I don't want to know about it. I think that if you're reincarnated, you're probably reincarnated as many times as you want to come back - once you've cleaned up your karma, your office. I think my grandfather is very close right now; I don't think I would have put country songs on my album if he wasn't. I try not to analyze it too much, but I think that for me, in the next life, it will be easier."

Stretched wearily on the couch in her hotel room and sipping white wine, Stevie looks as if she’s depending on that. "Sometimes you can't win--for the losing," she says somberly. And when all the veils between her sadness and her non acceptance are parted, and she cannot escape into the looking glass, she sometimes confides "in the unknown God, whoever he or she is. I don't go to church, but I am very religious. I was raised Episcopalian, but I went to Catholic schools here and there. I love Gregorian chants, and I write in chant structures, so I probably have been very religious in my time here during the last 3 million years. I pray when I'm upset about the outcome of my predicaments."

Among her many recent tribulations have been the voice problems she faced in the wake of Fleetwood Mac's incessant touring. And what made them especially upsetting were the nasty press notices that followed many of the shows in which her formidable vocals faltered or cut out altogether. Prior to joining-the-road-hungry group she had never had to push her voice. Four-month outings grew into trips triple that duration, and her ravaged vocal chords never had time to heal.

"My vocal muscles got so bad I would have to go to a throat specialist, especially before the LA Forum or the Garden. They would give me shots that deswell your chords enough to allow you to sing. But it’s not good to get those shots a lot with your chords in that shape. After two and a half hours of singing, you can shred them, truly blow them right out of your throat.

"The first time we played the Forum I went immediately to the doctor for all the preparations, and as I was leaving, he said [solemnly], 'Good luck, my friend.' I said to myself, 'I am in big trouble.' At rehearsal, Lindsey started playing 'Landslide' and I couldn't sing it. I burst into tears."

She began to have nightmares in which she would take the stage, open her mouth and nothing would come forth, the huge crowd and the band staring at her in silence. She was near despair when a friend guided her to a Beverly Hills specialist who prescribed a routine of rest between concert stands-three days on, two off-and constantly speaking a bit higher, at a decidedly ungravelly pitch. She got into the habit of hurrying from plane to hotel room, shutting all windows and doors, putting cotton in her ears and napping for as long as possible before the sound check.

All was well; her voice became stronger than ever before, but then she learned that a woman in Grand Rapids, Michigan was suing her for the rights to Stevie’s favorite composition, "Sara." The woman claimed she had written it and sent a copy of the lyrics to Warner Bros. in November 1978.

The suit raged for months, despite Steve’s numerous witnesses (including, Kenny Loggins) and a demo cut at producer Gordon Perry’s Dallas studio in July 1978. It was only a few months ago that the women’s lawyers finally gave up, stating, says Stevie, "We believe you."

"There were some great similarities in the lyrics," Stevie asserts, "and I never said she didn't write the words she wrote. Just don't tell me I didn't write the words I wrote. Most people think that the other party will settle out of court, but she picked the wrong songwriter. To call me a thief about my first love, my songs, that’s going too far."

As her legal problems were clearing up, she resolved to do as much with her eyesight. Since childhood, it has been very poor, and when she began to make headway as a performer, she left her unflattering eyeglasses as home. Now she wears semi-permanent contact lenses and the difference is jarring.

"I was blind before," she assures with a laugh and a shiver. "I never, ever saw an audience until I recently did the Forum with Tom Petty! I can't see past four rows, even with my contacts. It's neat to see better, but there’s not quite as much to hide behind as with my glasses, and that’s a little scary, cause you can see people's eyes.

For most of my life, every light blurred and became a star. I had this incredible light show going on because of the way I saw. Maybe that contributed to my magical outlook on life. "I don't look at anything but in a romantic way," Stevie continues, adding that a song on Bella Donna called "The Highwayman" is about the Eagles, the male members of Fleetwood Mac and other masculine rockers. "They are the Errol Flynns and the Tyrone Powers of our day!" she exults slyly. "So as long as I have to live with them, I try to make them into the most wonderful bunch of guys I can possibly think up!"

While most of the other material on Bella Donna was written in recent years (the sorrowful, supportive "Think About It" was done for Christine McVie in 1974 as her seven-year marriage to John was ending), "After the Glitter Fades" came about in 1973 (misdated as 1975 on the sleeve) and therefore provides a rare glimpse of Stevie's attitudes on stardom before she joined Fleetwood Mac.

The loneliness of a one-night stand

Is hard to take

We all chase something

And maybe this is the dream

The Timeless faces of a rock and roll

Woman..while her heart breaks

Oh you know...the dream keeps coming

Even when you forget to feel

The song sounds unusually mournful for someone beginning a career, and I ask Stevie if she was at a personal crossroads during that period. Nicks says that she was merely moving in the direction of an awakening that occurred a little more than a year later, just before she signed with Fleetwood Mac. She received a phone call on a Sunday afternoon from her Uncle Jonathan, who told her to find her brother and to fly immediately to St. Mary’s Hospital in Rochester, Minnesota, where her suddenly ill father was to undergo open-heart surgery the following morning at 6:30. Panicking, she scrambled to locate Christopher, and they eventually caught separate flights.

"In the six or seven hours it took to get there, I thought about my dad and the possibility that he might not live through that operation. I can't tell you how I felt."

She sets down her wine glass and gazes at the New York skyline, which gleams orange in the summit sunset.

"We were running down the hallways of St. Mary's to get to his room. We find my mother sitting there, all by herself, weeping and saying, 'He said to give these Greyhound cuff links to your uncle, and he said I could sell the car he bought me; I don't want it and he knows it.'

"Christopher, and I just stood there saying, 'He’s gone? He’s gone? We didn't get to say good-bye to him, just in case?' And then we had to sit in a somber gray corridor for ten hours and wait to be told... we didn't know what. When I went and a saw him, well, my dad’s not a complainer, he’s real strong, and he looked up at me and said, 'I'm in so much pain.' I couldn't do anything, so I went out and looked for lip gloss or something..." Her eyes redden, her shoulders slump and she begins to sob.

"From that day onward, I was never, ever the same," she says, trying to wipe away the stream of tears. "I'm sorry," she says with a cough, "this is not something I wanted to do. It was such a horrible thing for me and Chris and my mother; Chris passed out. Nothing else mattered; Lindsey didn't matter, music didn't matter, songs didn't matter, nothing mattered more. I said, 'Dear God, I would give everything up if you would just let me keep him for a little while.'

"Since that moment, he’s the one who gets the first albums, the first everything. I think I live on eggshells all the time, waiting to pick up the phone and have them say he’s gone. Every time I write him, I say that line from 'Crystal' I wrote for him: 'I have changed but you remain ageless.' To me, it says that this is what life is all about, because if somebody could take him away from me, they could do anything to me."

As Stevie Nicks composes herself, she acts a bit befuddled, as if the unexpected torrent of emotion has displaced her. She appears lost and more than a little forlorn. Despite her many friends and close family ties, she seems to move in her own exclusive sphere, a lonely, space not unlike "the big old house" she sings about in "Blue Lamp," a song of hers on the soundtrack of the science-fiction film Heavy Metal. Echoic, foreboding and sirenlike, it’s the sort of music you'd expect to hear ricocheting off the walls inside a haunted castle on a stormy night, when only a solitary blue lamp beats back the encroaching gloom. If Stevie’s songs really are "the mirror of her heart," as she maintains, then "Blue Lamp" is ominous but also offers some promise as she urgently intones, "I’m no enchantress!" and then advises the resident guardian angel, "If you were wiser, you would get out."

Stevie is at yet another crossroads, the significance of which only she can comprehend, but you wonder what turn she’ll take. And if you’re going to probe for answers, it's plain that you must ask for them on her terms.

There are, for instance, a lot of ways to look at Beauty and the Beast: you can view it as a tragedy, a morality play, a horror story. As it happens, a wealth of different versions exists. Jean Cocteau’s film ends on an uplifting note, the Beast turning into a handsome prince and living happily ever after with Beauty. But Stevie Nicks doesn't remember it that way. For her, the roles of the two star-crossed principals are transposed, and Beauty recognizes her folly too late, losing the only being besides her parent who truly loves her.

Sitting across from Stevie as she dries her eyes and slips back into here and now, I can think of only one appropriate question.

"In your version of Beauty and the Beast, Beauty finally understands that there are difficult choices to make in this world. Knowing her fate, if you were her, what would your decision have been?"

"I would have chosen the Beast," she says softly. "Absolutely."

| The Nicks Fix main page |